Fearing visa hassles could cost him his job in Dubai while an economic collapse had dashed any homecoming options, Lebanese executive Jad splurged around $135,000 on a new citizenship for himself and his wife.

Within a month of making the payment last year, the 43-year-old businessman received a small package in his mailbox.

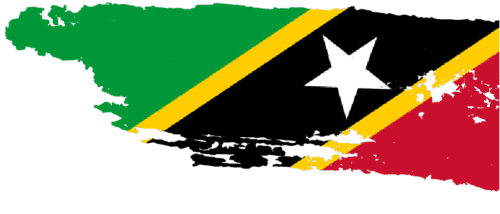

Inside were two navy blue passports from the Caribbean island nation of Saint Kitts and Nevis — his ticket to visa-free access to more than 150 countries, including in Europe.

This was a major upgrade from the Lebanese passport, which is ranked among the worst in the world and has become nearly impossible to renew because the cash-strapped state is running out of stocks.

“Three years ago, I would not have imagined I would buy a passport,” said Jad, who had previously grappled with lengthy visa procedures for business trips.

“But now because of the situation in Lebanon — and because we can afford it — we finally did it,” he said, asking for his full name to be withheld for privacy reasons.

A Saint Kitts passport ranks 25th in the world while Lebanon languishes at 103rd on the Henley passport index for freedom of travel.

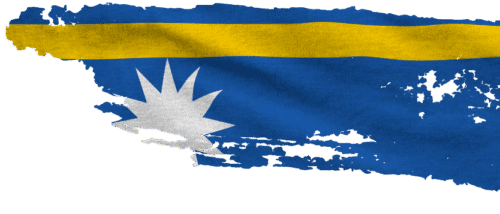

With a population of under 55,000, it started selling citizenships a year after gaining independence in 1983.

Citizenship by investment schemes have become a booming business internationally, attracting the well-to-do from volatile countries like Iraq, Yemen and Syria.

Some EU member states, including Bulgaria, Cyprus and Malta, have also operated “golden passport” schemes, but they have run into opposition from the European Commission over the back door they offer to EU citizenship.

Wealthy Lebanese, mostly living in Gulf or African nations, are now among those hunting for passports that offer easier travel and a safety net from the economic crisis at home.

‘Nice country’

Commonwealth Caribbean nations are particularly attractive because of their long-standing schemes offering citizenship within months in exchange for a lump sum.

Applicants are not even required to visit.

When Jad first went to Paris as a Kittitian, officers at passport control told him: “You come from a nice country.”

“But actually I have never been there,” he said.

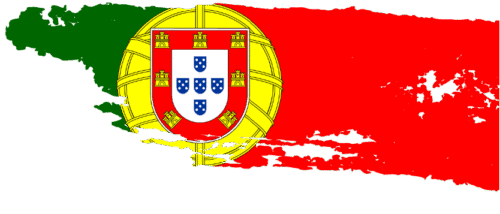

Jad’s Lebanese friends in the Gulf were also shopping for “island passports” or investing in real estate in Greece and Portugal to obtain residency as part of so-called “golden visa” schemes, he said.

“This is not just a trend. It’s a solution.”

Lebanese expatriates in Gulf Arab states have long borne the brunt of political bickering and rifts between their capitals.

Last year, several Gulf countries cut diplomatic ties with Beirut for months after a Lebanese minister criticised a Saudi-led military intervention in Yemen.

Kuwait limited the number of visas granted to Lebanese, and many in the diaspora worried other Gulf states would follow suit.

“That made me think: I have a problem here, I don’t want to jeopardise my work in the Gulf,” said Dubai-based businessman Marielli Bou Harb.

The 35-year-old bought Saint Kitts passports for his family of four last year, encouraged by a hefty discount as the Covid-19 pandemic beleaguered the island nation’s tourism-dependent economy.

A single passport usually costs around $150,000, a sum funnelled into a sustainable growth fund for the country, which only installed traffic lights in its capital Basseterre in 2018.

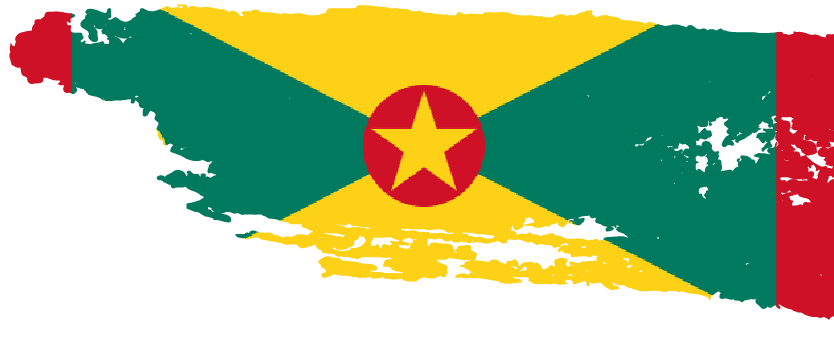

Other Caribbean islands including Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada and Saint Lucia also sell passports.

‘Buying their freedom’

Few people can afford such a purchase in Lebanon, a country in an economic crisis that has seen the currency nosedive, banks freeze deposits and most of the population fall into poverty.

Yet demand for foreign citizenship has spurred a boom in passport consultancy, with firms advertising on social media, billboards and even inside Beirut’s airport.

Among them is Global Pass, converted in 2020 from a real estate company after Lebanese started complaining of higher visa rejection rates.

“Our business has grown by at least 40 percent from 2020 to 2021,” said founder Ziad Karkaji.

Even international firms are raking in a profit.

Jose Charo, who heads the Beirut office of Swiss-based Passport Legacy, said Lebanese now account for one-quarter of the company’s clientele.

Their number has grown fivefold due to the economic crisis that was made worse by a devastating explosion at Beirut’s port in 2020, Charo said.

Having Grenadian citizenship makes applying for a US investor visa easier for businesspeople, he said, while those looking to retire or settle abroad can invest around a quarter of a million dollars in Greece or Portugal to secure permanent residency.

“The industry will keep on growing, unfortunately for this country but fortunately for us,” Charo said.

“They are buying their freedom.”